By Patrick Leary

This year the Curran Index has a special holiday surprise for Victorianists everywhere. In this latest update from longtime editor Gary Simons, the names of the authors of tens of thousands of unsigned contributions to three hugely influential Victorian periodicals — Punch, the Athenaeum, and the Saturday Review — are now freely available to researchers through the Curran Index database.

What’s New

The Index currently identifies the authors of almost 80,000 contributions (both prose and verse) published in Punch between 1848 and 1900. These were drawn from the manuscript ledgers in the Punch Collection of the British Library by Clare Horrocks, Valerie Stevenson, and their team at Liverpool John Moores University, who generously made their work available for integration into the Curran Index. There are many fun surprises here.

Few book reviews were more influential than those carried every week in the pages of the Athenaeum. With the cooperation of City University, London, whose library holds a marked file of the journal, and the generous assistance of Marysa Demoor of Ghent University, who made her own research available, over 58,000 Athenaeum articles (and some verse) published between 1830 and 1900 are now listed in the Curran Index. Much of this work involved painstakingly checking records against the notations in the volumes at City. The identifications now accessible through the Index include the astonishing record of novelist Geraldine Jewsbury, who published over 2200 reviews in the journal between 1848 and her death in 1880.

The famously disdainful Saturday Review holds a special place in the history of the Victorian press. Working with many different sources, Gary has assembled author identifications for over 4500 articles published from 1855 to 1900 in this much talked about magazine, including such prominent intellectuals as E. A. Freeman, Mark Pattison, Andrew Lang, and John Addington Symonds.

Attribution Matters

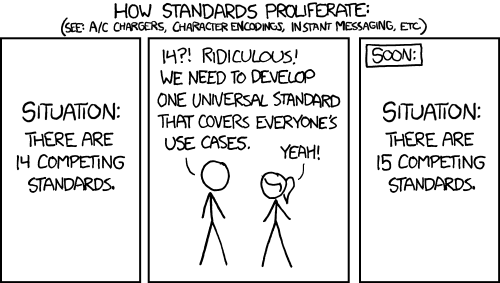

An unsigned essay of ‘Little Women’ would mean one thing if it was written by Harriet Martineau and quite another if the author turned out to be Eliza Lynn Linton. (Which, by the way, it did.) There’s a big difference between being able to write, “Popular playwright and longtime civil servant Tom Taylor observed in Punch that..” and instead having to write, simply, “Punch observed…” (Periodicals don’t write things; we only pretend that they do when we don’t know any better.) Thanks to this kind of work, many long-neglected authors as well as many others whose writings have been entirely unknown, are now emerging from the shadows of anonymity, opening up countless opportunities for fresh scholarly study.

These latest additions are the fruits of three years of steady work by Dr. Gary Simons. Gary’s remarkable editorship of the Curran Index — whose stages are documented, however briefly, in the Release Notes section of the site — will be coming to an end this year as he moves on to other projects. I’d like to take this opportunity (and future ones, too) to thank him for all that he has accomplished over the past seven years in building this extraordinary resource. Eileen Curran would be very proud.